NICE guideline [NG165]. The necropolitics of Covid-19 in England.

The government has been forced by the Covid-19 crisis to address the health of the public, but has done so through gritted teeth, spectacularly incompetently, and with its sights set doggedly on employing their friends and sponsors in private multinational corporations. Having done nothing to stop people with Covid-19 coming into the country, Johnson delayed the lockdown for as long as possible – a lockdown one week earlier would have saved 30,000 lives. (1) Decades of neoliberal policies have destroyed and fragmented the infrastructure that previously existed for providing public health services in a crisis.(2).

In February of this year, after long exposure to ideologically-driven depredations – fragmentation, commodification, outsourcing, privatisation, financialisation, bureaucratisation – the NHS and social care systems in England were in a parlous state. Though these were less publicised than in the previous winter, there were again queues of ambulances waiting to get acutely ill people into A&E departments, again people waiting for hours on trolleys and dangerously high levels of bed occupancy combined with severe understaffing.

Yet shortly after the peak of the first Covid-19 wave in April, Simon Stevens – one of those chiefly responsible for the ruination of the NHS in England – reported, “Last week emergency hospital admissions were at 63% of their level in the same week last year.” (3) At the same time, thousands of people – about a third of all the deaths from Covid-19 – most of them aged over 65, were dying of Covid-19 pneumonia in their own homes or in care homes up and down the country, looked after by family members, by visiting care workers, or by employed care home staff, most of whom lacked nursing training, had little or no access to oxygen or to palliative care drugs, and had inadequate PPE.(4) Thousands who might have been receiving a diagnosis even, or an adequate appraisal of the severity of their illness, and professional nursing care, adequate oxygen supply and monitoring, physiotherapy, or, if their condition worsened, expert palliative care, were denied all these things. Austerity has been well described by Ruth Wilson Gilmore as institutionalised abandonment. (5). Here we have a clear example of its practice on an unprecedented scale in terms of the harvest of deaths without adequate medical and nursing care that it facilitated.

By the term ‘necropolitics’ Achille Mbembe refers to the state, or its agents, exposing people to death or to social death, as a matter of policy, within the territories it controls (6). What follows is a provisional attempt to investigate how this intrusion of necropolitics into the health care system was achieved through professional guidance issued to GPs.

The National Institute of Clinical Excellence, (NICE) is an executive non-departmental public body of the Department of Health in England. NICE is widely respected by NHS staff and has generally functioned hitherto as a protective mechanism for the NHS from the exorbitant demands of the big pharmaceutical companies. It is a means, through its issuing of clinical guidelines, to try to ensure that health care professionals across the country work to constantly updated evidence-based standards.

NICE guidance, directed at primary care doctors, or their surrogates such as nurse practitioners or NHS 111 staff, called “COVID-19 rapid guideline: managing suspected or confirmed pneumonia in adults in the community, NICE guideline [NG165]” was published on 3rd April 2020 (7). There are likely many other relevant documents, such as local guidance issued at different NHS England levels – integrated care partnerships, or clinical commissioning groups, for example – and by professional bodies such as the British Geriatric Society,(8) which may have been effective in much the same direction. Directions and nudges were doubtless conveyed via other media than written guidance documents. Yet this NICE guidance is both central to and illustrative of the process that unfolded.

The document opens with a reassuring preamble, albeit in small print,

“The guideline does not override the responsibility to make decisions appropriate to the circumstances of the individual, in consultation with them and their families and carers or guardian.”

It goes on..

“The purpose of this guideline is to ensure the best treatment for adults with suspected or confirmed pneumonia in the community during the COVID-19 pandemic and best use of NHS resources. We have withdrawn our guideline on diagnosing and managing pneumonia in adults until further notice.” (My emphasis)

No further reason or argument is given for this withdrawal, and most importantly nothing is put in its place. As nudge theory has it, readers offered such a void are likely to adopt the default option, they are in effect being nudged towards doing nothing.

The guidance continues:

“2.1 When possible, discuss the risks, benefits and likely outcomes of treatment options with patients with COVID‑19, and their families and carers. This will help them make informed decisions about their treatment goals and wishes, including treatment escalation plans where appropriate.

2.2. Find out if patients have advance care plans or advance decisions to refuse treatment, including ‘do not attempt cardiopulmonary resuscitation’ decisions.

…………

4.1. Be aware that older people, or those with co-morbidities, frailty, impaired immunity or a reduced ability to cough and clear secretions, are more likely to develop severe pneumonia. Because this can lead to respiratory failure and death, hospital admission would have been the usual recommendation for these people before the COVID‑19 pandemic. (my emphasis)…(and note there is no replacement recommendation.)

4.2 When making decisions about hospital admission, take into account: the severity of the pneumonia, including symptoms and signs of more severe illness…. the benefits, risks and disadvantages of hospital admission…. the care that can be offered in hospital compared with at home….the patient’s wishes and care plans….service delivery issues and local NHS resources during the COVID‑19 pandemic.

4.3 Explain that: the benefits of hospital admission include improved diagnostic tests (chest X-ray, microbiological tests and blood tests) and respiratory support….the risks and disadvantages of hospital admission include spreading or catching COVID‑19 and loss of contact with families.”

The guidance notably fails to make any distinction between clinical assessment and decisions about treatment, which in any effective medical consultation are quite different phases. Often, because of lack of full PPE in the community, the doctor (or their surrogate) during this epidemic will have been consulting remotely using a telephone or a video link. They can still gather a history of the illness, though even this may be impaired by lack of hearing, by a poor connection, by the person having been alone and now sick, or by the absence of an interpreter, but effective examination is minimal. This limited capacity to provide any but an inadequate and provisional examination might reasonably be expected to lead to more emphasis being placed on the results of investigations – pulse oximetry to ascertain the level of oxygen in the blood, swabs of the nose and throat to look for Covid-19, blood tests (to look for anaemia, evidence of bacterial infection, bad diabetic control, or kidney problems), chest x-rays or a CT scan of the chest. It is after such an assessment, when the patient has maximised their knowledge about what is wrong with them, that the consultation or a series of consultations should go on to offer alternatives as to the nature and the site of their further care, leading up to the patient making a choice. These are basic sequences and well known features of adequate consultation practice, literally the basics of training in primary health care. How can a frightened and sick elderly person be asked to make a decision about their care, aided by their families if present, when they have not been given access to the necessary information to make it? The fear of separation, removal from known surroundings, and of a lonely death looked after by masked strangers, can readily be used to tilt the scales towards a decision to stay at home to face death or recovery without any NHS support, without them being able to notice or protest that key phases of an adequate consultation have been missed out.

Most of us are familiar with situations, after an accident or an acute illness, when we have to go to a designated place, usually an A&E department, to have an assessment, because x-rays or some other technology or expertise are required; after that, we can decide, or can be advised, to go home for the rest of the treatment. There is absolutely no reason why Covid-19 infection should have been any different – everybody who was significantly unwell, and the elderly disabled in particular, needed to have access to proper assessment before they could consider where the rest of their care was to take place. Moreover, those who decided to go home after such an assessment could at that point have been given PPE for their carers, to prevent further spread of the infection to them.

Quite a few people over the age of 65 have made Advanced Care Plans, after discussion with their GP, with the purpose of trying to ensure that they will not be subjected to futile or excessive treatment in the future, should they be in a situation where they have a terminal illness. Others will have signed ACPs at the time when they learn that they have such a terminal illness, following a sufficiently exhaustive series of investigations. Terminal illness here can mean incurable cancer, but it may also mean severe chronic lung disease, neurodegenerative disorders, or heart failure, for example. The basic assumption made about the occasion on which an Advanced Care Plan will become operative, is that the information available to the person concerned – or if they lack capacity, to their relatives – has been optimised on the occasion when it is brought into operation. To refer to ACPs in the same clause as ‘refusal of treatment’ is an iniquitous confounding.

Yet during March and April primary care teams were being encouraged to work towards signing up as many as possible of their disabled population over 65 years old to ACPs, which were to be taken as consent to the withdrawal of adequate assessment or any kind of hospital care, should they be suspected of contracting Covid-19.

The City and Hackney set of instructions to GPs based on these NICE guidelines and the British Geriatric Society guidelines on Covid-19 in care homes, a local bulletin issued by City and Hackney CCG on 1st May, urged them to get yet more ACPs signed (11). This went beyond reminding doctors of the the generally accepted and evidence-based notion that mechanical ventilation in people with a moderate level of frailty is futile, by suggesting that doctors should advise all moderately frail patients over 65 years old – those who have problems with stairs, need help with bathing, and need help with outdoor activities – that admission to hospital for any reason would be futile, and suggesting that they should sign up in advance that they would prefer to have care at home. A previous City and Hackney document issued on 20th April (12) had also asked GPs to consider that those with even just mild frailty – those who are rather slow and need help with such things as their finances, transportation, medication or heavy housework – should be encouraged to opt for ‘home treatment’ where possible, if they were later suspected of Covid-19 infection.

Reports emerging during March which suggested that batches of patients were being signed up for ACPs without any individualised discussions led to the publication of a joint statement from the British Medical Association (BMA) Care Provider Alliance (CPA) Care Quality Commission (CQC) Royal College of General Practice (RCGP) on 1st April to stop this abusive practice (9), but the statement did not address the mis-use of pre-existing plans, nor address the confusion between assessment and treatment, or between treatments that would be futile and other treatments that might be needed. Many who had already expressed the wish to die at home from their diagnosed conditions or from future terminal conditions long before Covid-19 had emerged, were also to be deemed, it seems, to have made the same decision in relation to this acute infection. This was a bureaucratic procedure facilitating an unethical interpretation of what advanced care planning means. People who signed an ACP in good faith, not in order to refuse assessment of their condition, but in order to avoid being subjected to futile treatment, had this ACP used to shut them off from any adequate assessment and from accessing other treatment, palliative or otherwise, that would be far from futile.

Those who could most clearly articulate their rights and their reasonable expectations of a functioning health service, or whose relatives or friends were there to advocate for them, would have been the ones who overcame these barriers and were sent to the hospital to be assessed. This is an example of what the late Julian Tudor-Hart in 1971 identified as the inverse care law, “The availability of good medical care tends to vary inversely with the need for it in the population served. This … operates more completely where medical care is most exposed to market forces, and less so where such exposure is reduced.”(10). Using a second language, existing disabilities of hearing, sight or cognition, and the weight of a lifetime of experiences of domination and abusive practices, all obviously militate against standing up for ones’ autonomy in these deliberations about whether you should be given care, especially when those discussions deliberately conflate assessment and treatment, and are unclear or even blatantly wrong about which kinds of treatment might be futile. This is guidance designed to limit access to care for the disabled and for the underprivileged, and may be one of many pathways that has led to the preponderance of BAME deaths observed during the epidemic.

Many doctors working in primary care across England will not have altered their practice at all because of this withdrawal of the guidance on treatment of pneumonia, because they use guidelines that give them useful information in responding ethically to the needs of the patient in front of them, and disregard those that fail in this respect. Likewise, many disabled people who called for emergency help, suspecting they had Covid-19, may have been able to insist on their need for a proper diagnosis and for better care than they could receive at home or in their care home. Many asked to sign up to ACDs in the weeks before the pandemic struck will have realised that it was not in their interest to do so.

Moreover the outcome at the height of the first wave of Covid-19 in England, seen in terms of the capacity of hospital services being under-utilised at a time when there were many dying of Covid-19 in the community, and particularly in care homes, may well have had more to do with the government’s reckless decision to order hospitals to discharge large numbers of elderly patients into care homes, thus greatly increasing the number of people likely to be infected by them. But the NICE guidance was pushing in the same direction – that is, creating a group that could and should be sacrificed for the greater good. If fashioning such a Pharmakon is a proper function of the state, then a critique of the moral basis of such a state is in order. Certainly it is not a function of a health service, which is meant to be the workplace of professionals, whether nurses, doctors, or others, who are meant to act with quite different ethical imperatives.

Boris Johnson and Matt Hancock have congratulated themselves that the NHS did not actually collapse in the face of the massive first wave of Covid-19 infections that they had allowed to happen. It is a bitter irony that NHS England, having been fragmented and commodified by a coterie of enthusiasts for US health care systems, such as Stevens, has resulted in its reaching a condition in which the accusations levelled at NICE and at the NHS by US cheerleaders for private health care – that they represent not just a systematic restriction of the free market, but a denial of the dignity and rights of service users – can at last seem to have some truth in them. Advanced Care Directives have been tarnished (13). From now they should carry a health warning: “This directive could seriously damage your health, as it can be interpreted as an invitation to institutionalised abandonment.”

References:

(1) Front. Public Health, 29 May 2020 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2020.00256 COVID-19 UK Lockdown Forecasts and R0. Greg Dropkin, Independent Researcher, Liverpool, United Kingdom

(2) Guardian, 31st May, 2020, Felicity Lawrence, Juliette Garside, David Pegg, David Conn, Severin Carrell and Harry Davies. “How a decade of privatisation and cuts exposed England to coronavirus.”

(3) Letter from Chief Executive Sir Simon Stevens & Chief Operating Officer Amanda Pritchard

to Chief executives of all NHS trusts and foundation trusts, CCG Accountable Officers,

GP practices and Primary Care Networks, Providers of community health services, NHS 111 providers, 29 April 2020.

4) Office for National Statistics, Statistical bulletin

Deaths registered weekly in England and Wales, provisional: week ending 22 May 2020

Provisional counts of the number of deaths registered in England and Wales, including deaths involving the coronavirus (COVID-19), by age, sex and region, in the latest weeks for which data are available. 2nd June, 2020

“The year-to-date analysis shows that, of deaths involving the coronavirus (COVID-19) up to Week 21 (week ending 22 May 2020), 64.2% (28,159 deaths) occurred in hospital, with the remainder occurring in care homes (12,739 deaths), private homes (1,991 deaths), hospices (582 deaths), other communal establishments (197 deaths), and elsewhere (169 deaths).“

(5). Ruth Wilson Gilmore on Covid-19, Decarceration, and Abolition. Webinar by Haymarket Books 17 April 2020

(6) Mbembe, Achille (2003). “Necropolitics”. Duke University Press, 2011.

(7) COVID-19 rapid guideline: managing suspected or confirmed pneumonia in adults in the community

NICE guideline [NG165] Published date: 03 April 2020 Last updated: 23 April 2020

(8) COVID-19: Managing the COVID-19 pandemic in care homes for older people

Good Practice Guide. British Geriatrics Society 30 March 2020

(9) British Medical Association (BMA) Care Provider Alliance (CPA) Care Quality Commission (CQC) Royal College of General Practice (RCGP) 1st April 2020 A joint statement on advance care planning –

“The importance of having a personalised care plan in place, especially for older people, people who are frail or have other serious conditions has never been more important than it is now during the Covid 19 Pandemic.

Where a person has capacity, as defined by the Mental Capacity Act, this advance care plan should always be discussed with them directly. Where a person lacks the capacity to engage with this process then it is reasonable to produce such a plan following best interest guidelines with the involvement of family members or other appropriate individuals.

Such advance care plans may result in the consideration and completion of a Do Not Attempt Resuscitation (DNAR) or ReSPECT form. It remains essential that these decisions are made on an individual basis. The General Practitioner continues to have a central role in the consideration, completion and signing of DNAR forms for people in community settings.

It is unacceptable for advance care plans, with or without DNAR form completion to be applied to groups of people of any description. These decisions must continue to be made on an individual basis according to need.”

(10) Tudor Hart, J. (1971). “The Inverse Care Law”. The Lancet. 297: 405–412. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(71)92410-X. PMID 4100731.

(11) City and Hackney CCG Bulletin for GPs, issued 1st May 2020, section on Advanced Care Planning.

(12) COVID-19 primary care guide to decision making around escalation priorities, advance care planning, palliation and end of life ,16th April 2020

The aim of this is a guide is to support GPs with advance care planning prior to COVID-19 infection. It also considers when to convey to hospital those patients who do not have a Coordinate My Care (CMC) plan in place but have a history that put then in the high-risk group with a degree of frailty. City and Hackney CCG, Homerton University Hospital Foundation Trust, and City and Hackney GP Confederation.

(13) British Geriatric Society. Did the UK response to the COVID-19 pandemic fail frail older people? 14th May 2020. Rowan H Harwood

The Separation wall in Abu Dis from the viewpoint of a demolished house. Beyond the wall, on the horizon – near to the protection of the Israeli army camp that is this side the wall under the radio mast and dominating Abu Dis – is a US settler’s house near the Wall. In what was once a farm house – the white building in a clump of small trees – an Arab family manages without water and electricity, but so far prevents by their presence and ownership of the land the planned building of a planned much larger Israeli settlement.

The Separation wall in Abu Dis from the viewpoint of a demolished house. Beyond the wall, on the horizon – near to the protection of the Israeli army camp that is this side the wall under the radio mast and dominating Abu Dis – is a US settler’s house near the Wall. In what was once a farm house – the white building in a clump of small trees – an Arab family manages without water and electricity, but so far prevents by their presence and ownership of the land the planned building of a planned much larger Israeli settlement.

Looking back through the checkpoint for pedestrians between Abu Dis and East Jerusalem.

Looking back through the checkpoint for pedestrians between Abu Dis and East Jerusalem.

Al Khan al Ahmar school – still standing after last year’s desperate campaign and international outcry, but still under threat of demolition.

Al Khan al Ahmar school – still standing after last year’s desperate campaign and international outcry, but still under threat of demolition. Jabel Al Baba view over to settlement.

Jabel Al Baba view over to settlement.

Settlement over Wadi Abu Hindi village, from which diverted sewage has been poured at times, and – when a marquee was set up for a wedding – burning tyres.

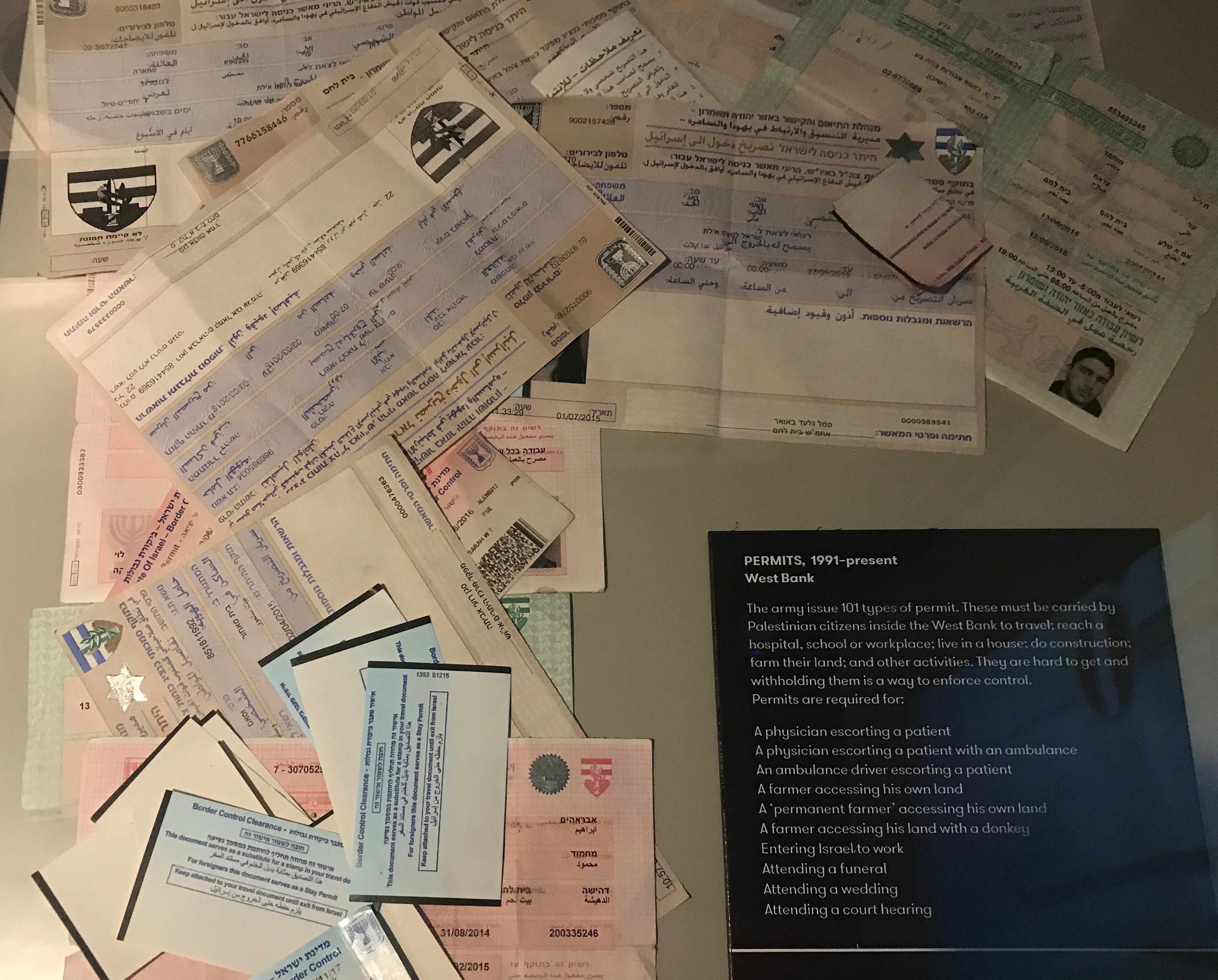

Settlement over Wadi Abu Hindi village, from which diverted sewage has been poured at times, and – when a marquee was set up for a wedding – burning tyres. Picture of array of passes from Walled-Off hotel exhibition

Picture of array of passes from Walled-Off hotel exhibition

Children going through a gate in Hebron into the guarded settlement area where some Palestinian Arabs still have their homes, here a child was killed last year who did not understand instructions shouted in Hebrew.

Children going through a gate in Hebron into the guarded settlement area where some Palestinian Arabs still have their homes, here a child was killed last year who did not understand instructions shouted in Hebrew. Young woman hand on gate in Hebron.

Young woman hand on gate in Hebron. Hebron access gate in the ruined market area near Shuhada Street.

Hebron access gate in the ruined market area near Shuhada Street. Courtyard with objects on the roof picture

Courtyard with objects on the roof picture Doorway into shared courtyard where a child’s arm was burned with acid thrown by a settler youth living above.

Doorway into shared courtyard where a child’s arm was burned with acid thrown by a settler youth living above. Israeli flags on house in Via Dolorosa in the heart of the Arab quarter of the Old City

Israeli flags on house in Via Dolorosa in the heart of the Arab quarter of the Old City House demolitions

House demolitions

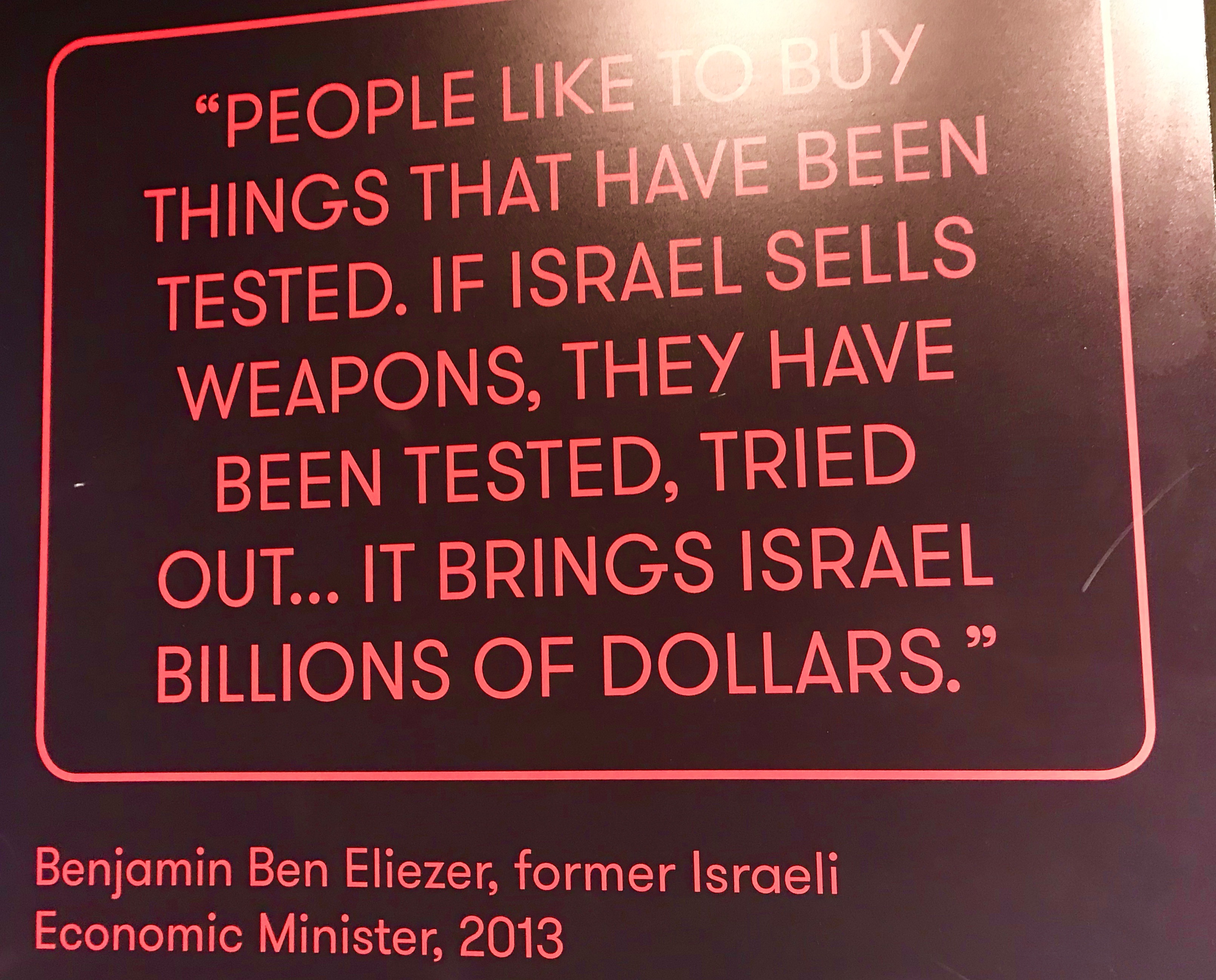

Finance minister statement 2013 exhibit at Walled-Off museum

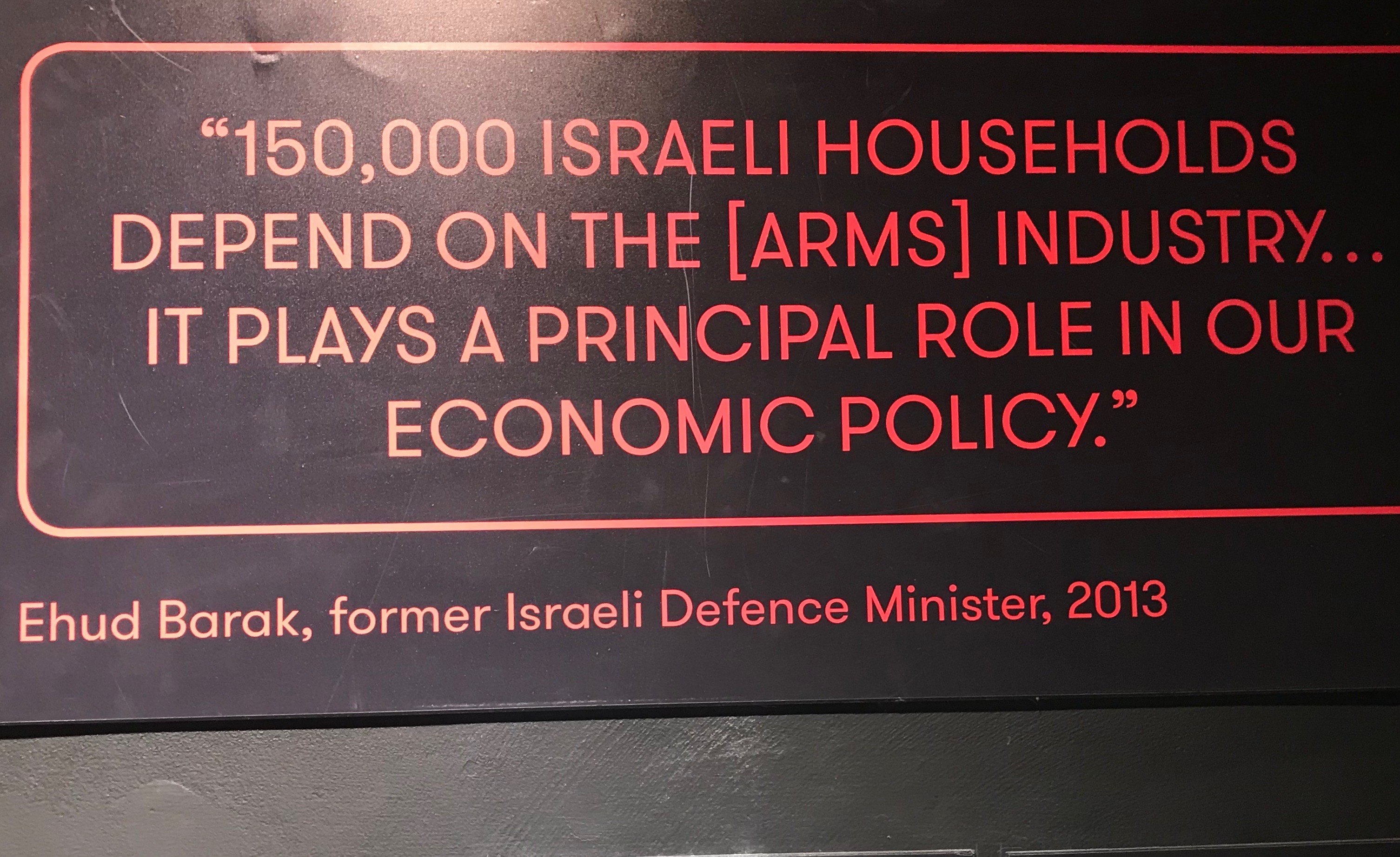

Finance minister statement 2013 exhibit at Walled-Off museum Ehud Barak statement on arms industry exhibit at Walled-Off museum.

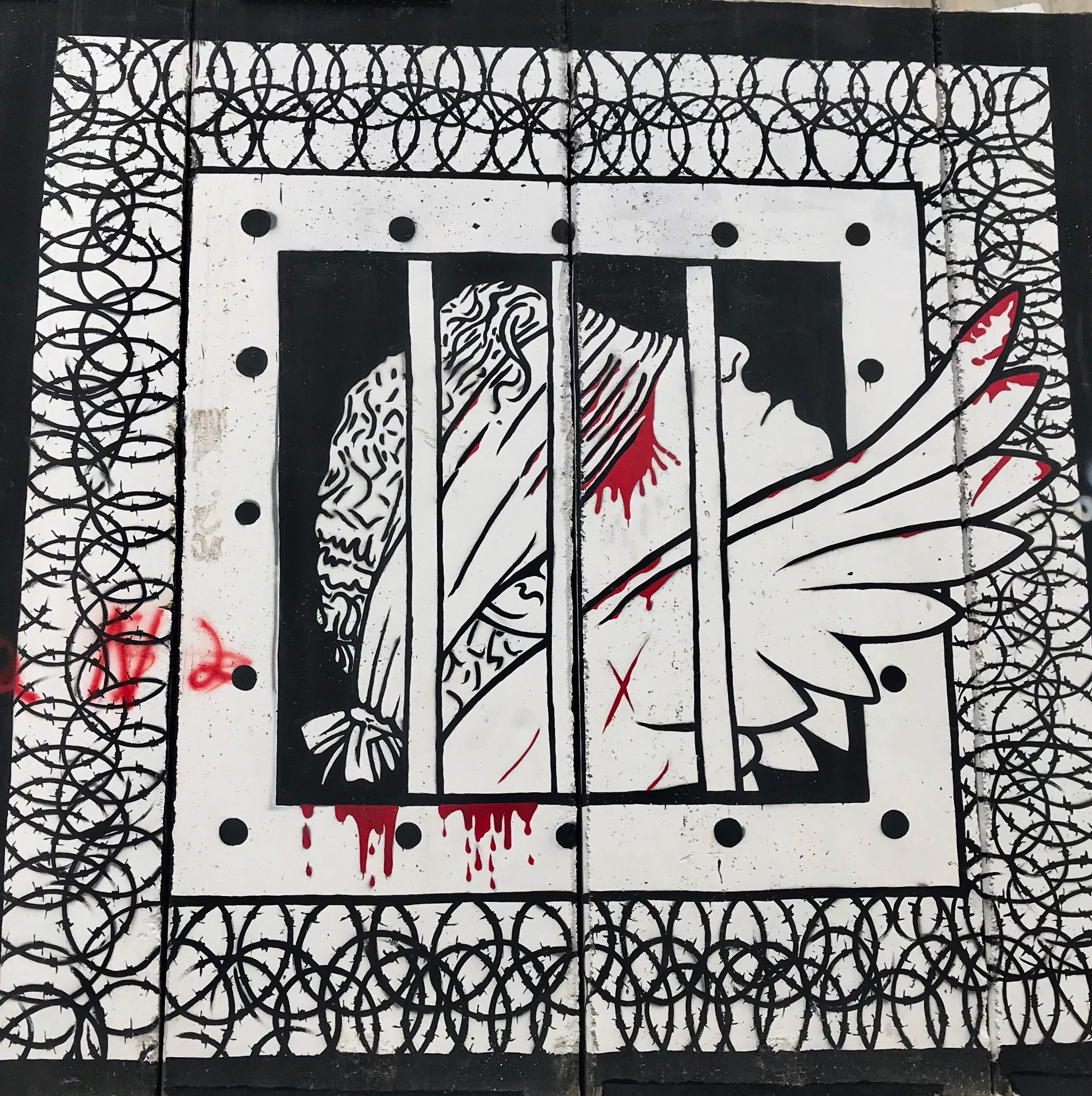

Ehud Barak statement on arms industry exhibit at Walled-Off museum. *** [art on wall at Bethlehem photo]

*** [art on wall at Bethlehem photo]

Water containers on the rooftops – the marker of a West Bank Arab community.

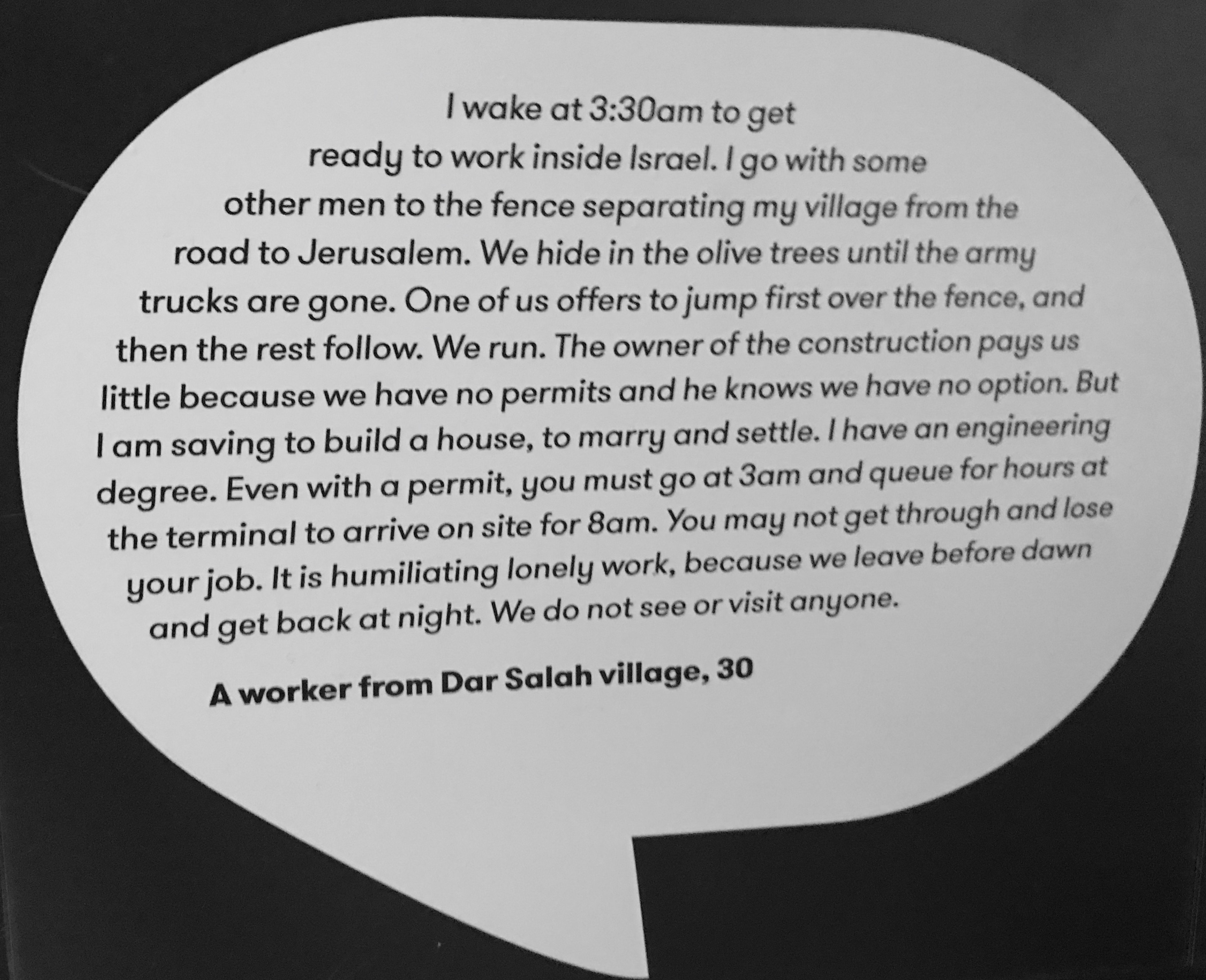

Water containers on the rooftops – the marker of a West Bank Arab community. Exhibit of one man’s account in Walled-Off Hotel.

Exhibit of one man’s account in Walled-Off Hotel. Settlers with assault rifle in the countryside.

Settlers with assault rifle in the countryside.